The Price of the Ticket

by Mone’ Anderson and Erica R. Meiners

Despite the neon warning signs—an embedded billion-dollar product line and a marketing campaign leashed to Disney and Marvel empires—we both anticipated Black Panther.

Erica, a long time fan of radical sci-fi films—think Brother from Another Planet , Space Is the Place, or her favorite Born in Flames— wanted to see how Ryan Coogler, the director of the aching Fruitvale Station about the life and death of Oscar Grant, would build (with a mega budget of $200 million dollars) a world outside of white supremacy.

Mone’ also wanted to see how Ryan Coogler would use Afrofuturism to reconstruct and center the narratives of Black culture through a lens of liberation. Too often Black kids grow up in low-income neighborhoods—their schools closed and opportunities pulled away—but they prevail. More than a movie, Black Panther gave Black people a space to re-imagine a world where we were no longer oppressed and marginalized.

And our resulting praises aren’t totally empty. The opportunity to not just imagine but to feel and see a world outside of the endless project of white colonization—a task of many, including Octavia Butler, Leanne Simpson, N.K. Jemisin—is revolutionary. Black Panther (BP) centered (facets of) Black life, Black beauty, Black brilliance, Black humor, Black women, and Black ingenuity. BP employed Black actors (and, we hope, at least some Black crew). And while this is not necessarily new on the screen as we think of the L.A. Rebellion and the films of Julia Dash, Charles Burnett, Larry Clarke—and the beauty of Dee Rees’ Pariah (2011)—these representations never achieve mass circulation and (white) dollars.

Yet as queers, abolitionists, and feminists—one white and one Black—we raise three interrelated questions for discussion. We acknowledge, of course, that these are queries we do not take the time to register publicly against whitestream films that originated from the same corporate cauldron: Wonder Woman, Thor, or even the disastrously perpetual Star Wars. Engaging with films such as Black Panther is particularly important, because as Mone’ notes, for years, Black folks watched white platforms, not passively, create media that erased the talent, labor, and existence of Black folk.

The Enduring Violence of White Innocence

BP rehearses a familiar narrative of the rejection of “violence” as a strategy for oppressed peoples to achieve liberation; a move amplified by the deft erasure of the everyday forms of state violence that also define life in in the U.S. and in Wakanda. (By everyday violence in Wakanda we name, for example, the existence of borders, militaries, and cages, but also the practice of inherited power—a monarchy—with a resulting class/caste system). With an abundance of wealth, brilliance and magical vibranium, Wakandians have seemingly neither imagined nor built different ways to deal with a range of forms of harm—structural or individual. While dismissing the tools for survival and freedom deployed by oppressed peoples as terrorism, BP reifies forms of state violence.

This familiar representation flattens our understandings of harm, particularly those experienced by non-white communities. BP ignores the profound ways the U.S. nation-state continues to target Black (and other) liberation movements—domestic and not—for extinction. Framing the resistance and survival tactics of oppressed peoples as “violence” while masking harm of the state is an old story. We are reminded of the anger and astonishment of then incarcerated scholar and activist Angela Davis, when she is asked by a Swedish journalist and filmmaker whether she “condones violence” in the early 1970s (as preserved in the documentary film The Black Power Mixtape):

If you are a black person and live in the black community all your life and walk out on the street every day seeing white policemen surrounding you . . . when I was living in Los Angeles, for instance, long before the situation in L.A. ever occurred, I was constantly stopped. No, the police didn’t know who I was. But I was a black woman and I had a natural, and I suppose they thought that I might be “militant.” You live under that situation constantly, and then you ask me whether I approve of violence. I mean, that just doesn’t make any sense at all. Whether I approve of guns? I grew up in Birmingham, Alabama. Some very, very good friends of mine were killed by bombs—bombs that were planted by racists. From the time I was very, very small, I remember the sounds of bombs exploding across the street, our house shaking. I remember my father having to have guns at his disposal at all times because of the fact that at any moment, we might expect to be attacked. . . .That’s why, when someone asks me about violence, I just find it incredible.

As Davis’s comment pointedly asks—who gets to define violence? What forms of violence are visible, or not, and to whom? And, as her tone and response to the journalist indicates, the audacity of this question indicates there is no place for oppressed people to be outraged, or to even be able to name, the sheer weight of the violence of the state.

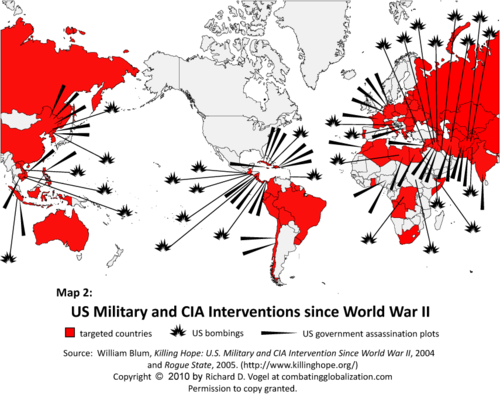

BP’s legitimization of the CIA compounds this erasure of the systemic, brutal, and naturalized forms of state violence that explicitly target Black communities. Why are the harms—historic and ongoing—of the CIA never made visible? Targeted assassinations, torture, domestic wiretapping, kidnapping, “extraordinary rendition”—in Oakland, Congo, Dominican Republic, and many many other non-white communities and nations—through the film’s logic, the CIA requires more scar marks than Killmonger. In contrast, Killmonger’s self-mutilation is presented in the film as evidence of his inherent violence, a deranged celebration of evil—rather than potentially more complex readings (a visceral practice of accountability? transparency? trauma from living under imperialism?). And while Killmonger’s goals are convoluted (personal power, vengeance, or Black folks’ freedom?), the CIA’s have historically been crystal clear: advance white supremacy and (white) capital, through militarism, at all costs. Yet despite these facets and histories, it is CIA Agent Ross, not Killmonger, who is somehow redeemable. Worse, the CIA, marked throughout the film as naïve, buffoonish and often as neutral, is never visibly part of the problem of an oppressive and lethal global world order, and instead is framed by the film as key to subjugated people’s global liberation movements.

LAPD Ramona Gardens Shop with a Cop Back to School

The film’s commitment to viewing one of the more toxic facets of the U.S. nation state as an ally—an “Officer Friendly” move—packs the worst punch at the close of the film when the trio—T’Challa, Nakia and Okoye—arrive at the United Nations to “come out” and pledge to aid and to change the world. The camera pans to a smiling and nodding Agent Ross in the audience. The CIA, devoid of any historical baggage, always an innocent actor, and most recently the savior of Wakandians, is a legitimate and necessary entity to conscript in the project of the global movement for the liberation of Black people. Ouch.

Abolitionist Longings

For many of us, abolition is not simply the taking down of prisons but the building of other forms of accountability, practices, and muscles to prevent and to respond to harm and violence. Contemporary abolition movements work to stop new jail constructions, to support sentencing reforms that get more people free, to shrink and end our reliance on punitive and racialized systems such as policing or child protective services, and to name and dismantle how carceral logics shape our schools, workplaces, and families. But an abolition politic and practice also strives to build transformative practices, or forms of community accountability, to hold people that have done harm accountable, and to build opportunities to transform the conditions that made harm possible. Viewing no-one as inherently disposable, an abolitionist politic and practice rejects retribution as a practice of accountability, and invites other opportunities. Like the visionary poet and scholar Fred Moten, we know that abolition demands a radical imagination and deep structural shifts.

What is, so to speak, the object of abolition? Not so much the abolition of prisons but the abolition of a society that could have prisons, that could have slavery, that could have the wage, and therefore not abolition as the elimination of anything but abolition as the founding of a new society (Moten and Harney 2011, 3).

Given this commitment, we are challenged that in this more perfect society, T’Challa, and therefore Wakanda by association, are willing to let Killmonger die. “Bury me in the ocean with my ancestors who jumped from ships, ’cause they knew death was better than bondage” is Killmonger’s last line in the movie. Clearly T’Challa can save lives, and is willing and able to for the CIA’s Agent Ross, but Killmonger is disposable.

Much ink has already been shed about Killmonger’s callous ability to kill his female lover and ally early in the film. Perhaps this killing is more outrageous because the leading cause of death for women is at the hands of the men who profess to love them. Yet as feminists committed to ending gendered and sexual violence, we know that the premature death and endless caging offered by the prison industrial complex is not a solution. The carceral state does not reduce gendered violence nor challenge the ideological structures—racialized heteropatriarchy for example—that naturalize violence against women. In our communities we engage and invest in transformative justice and community accountability models—however partial and messy—as tools and systems to build meaningful responses to gender violence. In our Black feminist utopia it is not simply that no-one is disposable, but our communities work to make visible and dismantle the belief systems and institutions that naturalize and reproduce gendered violence.

Related, why is our vision of a land that has never been colonized by white people a monarchy? Perhaps kingdoms are an inescapable constraint of the blockbuster-comic-film-genre, but hereditary power and privilege do not lead to equitable living conditions for all. As Moten alludes to, if we want abolition we must be willing to re-imagine and rebuild all the beliefs and systems that make prison imaginable and logical. Correspondingly, in order to end colonization and white supremacy, what would community, “governance,” self-determination, and the public, resemble? We do not believe that a monarchy is the vehicle that will get us, or keep us, free.…At the close of the film, when T’Challa brings his sister Shuri to Oakland and literally gifts her the right to run what can only be viewed as a charitable non-profit dedicated to the uplift of poor Black people, we wince. Noblesse oblige, even from benevolent monarchs (including fabulously cute and brilliant techie princesses), isn’t going to produce the fundamental redistribution of power and privilege that we need.

Anti-Queerness, Black Bodies & Capitalism

We were not surprised that queer portions of the comic storyline written by Roxanna Gay were not included in this film. The rumor mill suggests that a scene between two lovers and members of the Dora Milaje, Okoye and Ayo, was cut out of the final version. Can queers command the billion-plus global marketplace?

Opening weekend, Black Panther brought in $22 million, and as we write its worldwide profit rings in at over $1 billion. Some (white and Black, queer and not) would like to us to believe that the same people would show up and pay up for Black Panther if central characters were vibrantly queer, but we are not convinced. Of course our goal is not to queer the Marvel empire, a form of “pinkwashing” that is not liberatory. Rather, we raise the engineered disappearance of Black queers in BP, and the concurrent insistent reproduction of stale forms of heteropatriarchy, because in our movements for freedom, Black queer people show up time and time again for Black (and white) cishet folk—Opal Tometi, Mary Hooks, Charlene Carruthers, and Laverne Cox, for example. And, we suggest that these are the respectability tentacles of (whitestream) capital. The Disney fiefdom will not sanction representations that alienate audiences. Critiques of the CIA, self-determination outside of a monarchy, queer love—all pose potential market conflicts as they might alienate white dollars—and could shrink revenue.

We worry about leveraging any critique of the film’s elevation of respectability politics, a discourse that flourishes across many representations, and is not in any way, shape, or form restricted to communities of color. And even though this is a film orchestrated out of the whitestream film industry, any critique may easily stick to Black participants (who do hold some accountability) but never to the lines of racialized capital that form the foundation for BP. Too often, white queers focus on the lack of queerness without understanding the interrelated systems, such as white supremacy, which make these racialized queer spaces possible.

Yet, particularly when Black queer feminism is—as always—vibrant in “leaderful” movements, to quote the historian Barbara Ransby (2015), BP’s silence around Black queerness, and its hollow reinforcements of tired and traditional heteropatriarchal kinship networks, ring out. T’Challa is propped up by heteronormative and gendered familial scripts: the ingenious younger sister, the loving mother who will do anything for her son, the smarter (ex)girlfriend, and the stalwart “best friend” female ally (the General). The ancestral advisors? The patriarchy. The work of the world is “as common as mud” and is done by women, as poet Marge Piercy reminds us in “To be of use” (1982), but in BP the women do not love each other the way they love the central man in their lives, or the heteropatriarchal state he controls. The ongoing costs of this queer dismissal in our public spheres mount: Black transgender women have a life expectancy of thirty-five years and Black queer folk are more likely to experience homelessness than any other community (Inter American Commission on Human Rights, 2014, December 17).

We raise these overlapping critiques as the price of the ticket to see BP, to borrow a line from the title of James Baldwin’s 1985 collection of essays. For us, on some days, the cost is too high—swallow the (white) innocence of the CIA, the unpalatability of Black queer folks, the valorization of inherited power over self-determination, the failure to imagine radical responses to harm outside of punishment, and more. And the price of this ticket is not without the ubiquitous and extra Black tax. Whitestream audiences enjoy BP—Black beauty and Black power—without being implicated in any forms of structural white supremacy. Agent Ross (who is saved by Black power) is not only a hero but is key to our collective futures. Double ouch.

Work Cited

Baldwin, James. (1985). The Price of the Ticket: Collected Nonfiction, 1948-1985. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Harney, S., & Moten, F. (2013). The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning and Black Study. Brooklyn, NY: Autonomedia.

Inter American Commission on Human Rights. (2014, December 17). An overview of violence against LGBTQI persons: A registry documenting acts of violence between January 2013 and March 2014. Retrieved from: http://www.oas.org/en/iachr/lgtbi/docs/Annex-Registry-Violence-LGBTI.pdf

Piercy, Marge. 1982. “To be of use,” in Circles on the Water. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

The Black Power Mixtape 1967–1975. 2011. DVD. Directed by Göran Olsson. Sweden: Story ABT.

Ransby, Barbara. (2015). “Ella Taught Me: Shattering the Myth of the Leaderless Movement.” Colorlines. June 15. Retrieved from: https://www.colorlines.com/articles/ella-taught-me-shattering-myth-leaderless-movement.

ARTICLES

The Courage to Invent the Future

Killmonger's Captive Maternal Is MIA

Eulogy for Wakanda/The King Is Dead

What Don't Make Dollars Don't Make Common Sense

Dream Work: Fantasy, Desire and the Creation of a Just World

A Crisis in Hollywood: Black Panther to the Rescue?